By Madara Dias, MHR Program, University of Manitoba

Date: July 7, 2025

Introduction: From Maritime Power to Human Security

In Part 1 of this blog series, we examined the growing militarization, strategic

alliances, and infrastructure-led rivalries reshaping the Indo-Pacific. In this

second installment, we pivot to one of the most protracted and politically

sensitive humanitarian challenges in the region which consider as the Rohingya

refugee crisis in Bangladesh. More than a crisis of displacement, it is now a

test of Indo-Pacific diplomacy, regional security cooperation, and the future

role of small and medium states in managing complex emergencies.

The Rohingya Crisis: Humanitarian Emergency in a Strategic Theatre

As of mid-2025, nearly one million Rohingya refugees remain in Bangladesh, with

little progress made toward safe and voluntary repatriation. These refugees

reside in the world’s largest refugee camp complex in Cox’s Bazar, where they

face growing risks from malnutrition, trafficking, environmental hazards, and

camp violence. According to UNHCR, more than 95% of refugees rely entirely on

humanitarian aid, and food rations were cut to $8 per person per month in early

2024, worsening malnutrition, especially among children and pregnant women.

New threats such as cyclone damage, fires, and organized criminal networks

trafficking people to Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Middle East have emerged.

The camps, once viewed as temporary, are now sites of political fatigue and

diplomatic stagnation. This inaction contributes to instability and makes the

Rohingya vulnerable to extremism, exploitation, and statelessness, while also

complicating Bangladesh’s internal politics and regional diplomatic posture.

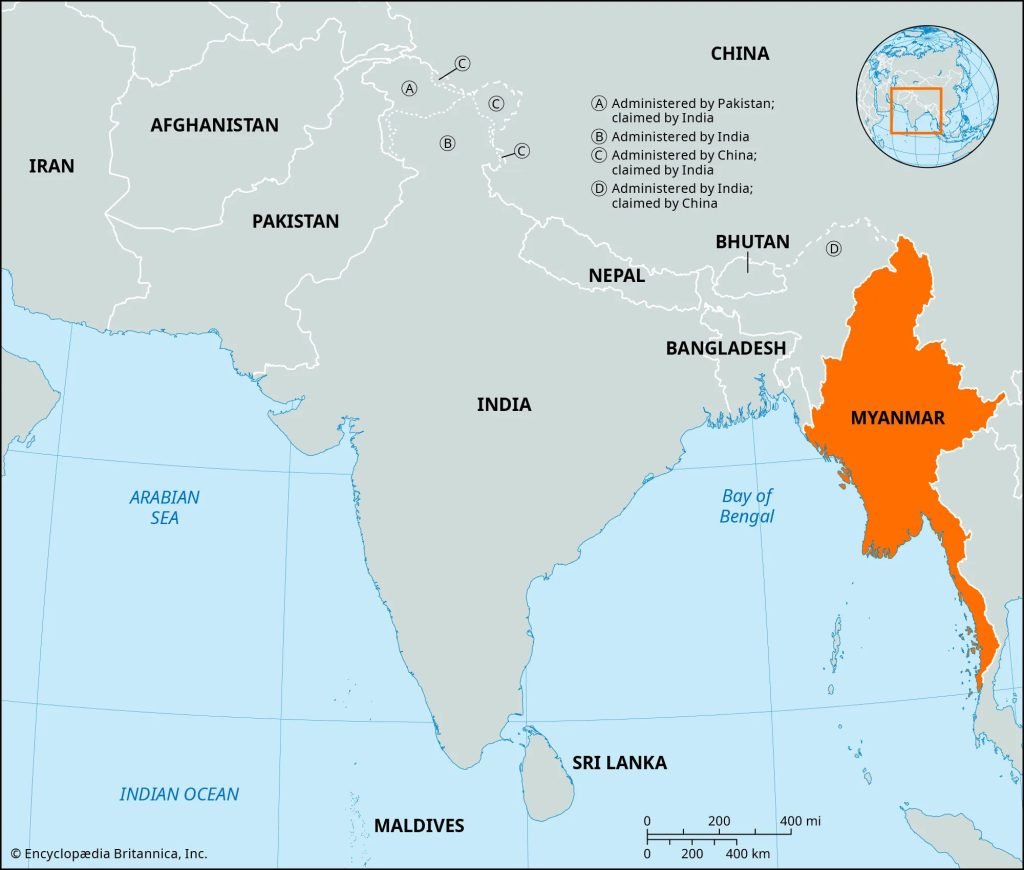

Myanmar’s Internal War and China’s Strategic Grip

Myanmar’s post-coup civil war has made repatriation of Rohingya refugees even more

implausible. The junta’s control over Rakhine State has weakened in the face of

Arakan Army offensives, leaving a power vacuum and escalating clashes that have

displaced tens of thousands more in early 2025.

Despite these tensions, Myanmar confirmed in April 2025 that 180,000 Rohingya refugees

could be eligible for return which is a gesture largely seen as symbolic rather

than actionable, given the security risks and lack of citizenship guarantees.

China remains Myanmar’s most influential external actor. Through the China–Myanmar

Economic Corridor (CMEC), an offshoot of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing

has secured control of the Kyaukphyu deep-sea port, oil and gas pipelines, and

road infrastructure that enable strategic access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing

the Strait of Malacca. China’s consistent support of the junta, both

diplomatically and through arms sales, underscores its long-term interest in

securing maritime access and countering US and Indian influence in the region.

This entrenched engagement makes China a gatekeeper to any international peace

effort in Myanmar, while sidelining global institutions like the UN or ASEAN

from meaningful influence.

Bangladesh:

A Pivot State Under Pressure

Bangladesh, which has shouldered the Rohingya crisis since 2017, is now experiencing donor

fatigue, domestic backlash, and geopolitical balancing stress. While Dhaka

engages with China through BRI infrastructure, such as the Padma Bridge, Payra

Port, and railway links, it also cautiously entertains the US-led Indo-Pacific

Strategy (IPS), participating in defense dialogues like GSOMIA and ACSA.

This dual alignment places Bangladesh in a precarious position: dependent on foreign

aid for humanitarian assistance, and yet wary of becoming entangled in great

power rivalries.

A growing debate within Bangladeshi strategic circles revolves around the idea of

a “safe humanitarian corridor” in Myanmar’s Rakhine State is an initiative

floated in past Track II dialogues. Proponents argue this corridor could serve

as a bridge for peace, supported by neutral countries or UN mechanisms. But

critics warn of foreign military presence near the sensitive Chittagong Hill

Tracts, and possible violations of national sovereignty.

As General Mahfuz noted in a recent webinar hosted by the Conflict and Resilience

Research Institute Canada, Bangladesh lacks a “credible deterrence

capacity” and a strong strategic culture, which limits its ability to push

for repatriation or humanitarian diplomacy assertively.

Multilateralism and Canada’s Diplomatic Niche

Among Western actors, Canada has taken a value-based soft power approach, especially

under its Indo-Pacific Strategy (2022). Through its “Path to Lasting Peace in

Myanmar” project, Canada committed CAD $56.8 million between 2023 and 2025 to

support Myanmar civil society and provide Rohingya youth with skills training

and livelihood assistance. However, observers have criticized the lack of a

special envoy, as previously promised, to coordinate Canada’s engagement and

policy leadership in the crisis.

ASEAN, despite repeated declarations, has made little tangible progress. Its “Five

Point Consensus” with the Myanmar junta remains largely ignored. Malaysia,

Thailand, and Indonesia which are the countries directly affected by Rohingya

migration and have called for more assertive diplomacy. However, ASEAN’s

principle of non-interference continues to hamstring collective action.

The Rohingya issue demonstrates the need for a reimagined multilateralism, one

where soft power states like Canada, mid-tier actors like Japan and South

Korea, and ASEAN members coordinate efforts on repatriation, aid, and

accountability.

What Needs to Be Done: From Stalemate to Solution

To avoid indefinite limbo, key stakeholders must pursue a multi-pronged, practical

strategy:

- Reframe the crisis as regional:

Encourage ASEAN and BIMSTEC to integrate refugee issues into regional

disaster management, border stability, and health security agendas. - Empower Bangladesh diplomatically:

Equip Dhaka with negotiation support, legal frameworks, and UN-backed

repatriation templates that hold Myanmar accountable. - Establish humanitarian monitoring mechanisms: A third-party oversight group (possibly

involving Canada, Japan, and Malaysia) could monitor conditions in Rakhine

State and verify return readiness. - Invest in refugee self-reliance:

Shift some aid toward education, employment, and climate-resilient

infrastructure for both host and refugee populations to reduce dependency. - Hold perpetrators accountable:

Support ICC proceedings and targeted sanctions that apply consistent

pressure on Myanmar’s military leaders, regardless of geopolitical

discomfort.

Conclusion:

Regional Future Hinges on Local Justice

The Rohingya crisis is no longer an isolated tragedy, it is a regional challenge

embedded in the Indo-Pacific’s strategic logic. The policies of Beijing, New

Delhi, Washington, and Ottawa all intersect in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar

and the conflict zones of Rakhine State.

If ignored, the crisis could become a flashpoint for militancy, human trafficking,

and diplomatic fractures. But with coordinated regional effort, diplomatic

courage, and a shift from reaction to prevention, this challenge could become

an opportunity for inclusive cooperation.

As we navigate the Indo-Pacific crossroads, ensuring dignity, safety, and justice

for the Rohingya will define whether the region chooses confrontation or

collaboration as its guiding ethos.

Stay tuned for our next post, which will explore the future of refugee diplomacy and

Bangladesh’s evolving role in humanitarian leadership across South and

Southeast Asia.